“Crafting Public Narrative to Enable Collective Action: A Pedagogy for Leadership Development”

Academy of Management Learning & Education

Action Insights

Last Updated

Topic

Strategic Leadership and Management

Location

Global

Why do some words move people to action while others are quickly forgotten? A study supported by the Bloomberg Harvard City Leadership Initiative proposes “public narrative” as a key form of leadership development in organizations and communities.

Read the Action Insights below, or download as a PDF for use later.

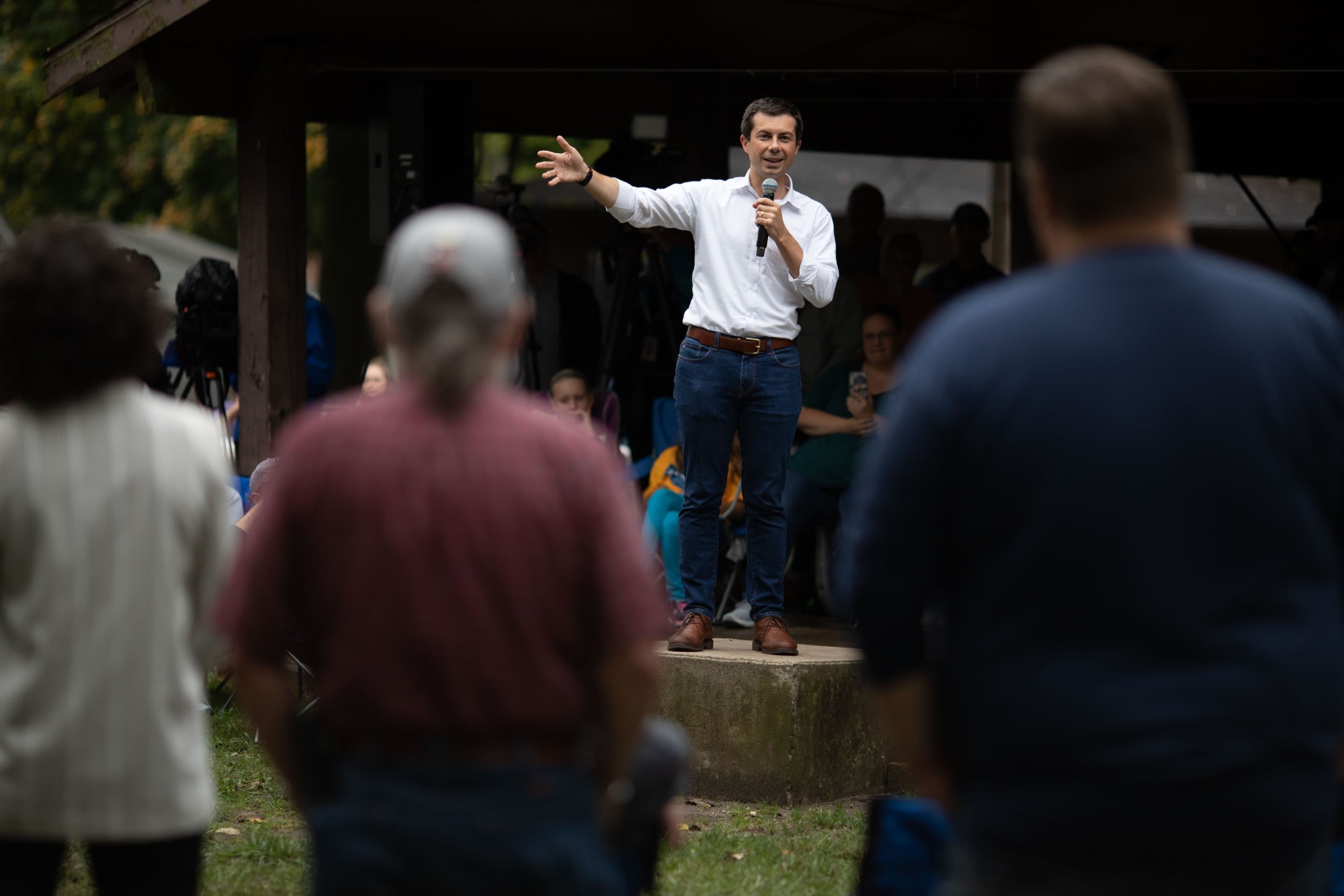

It was the spring of 2019, and Mayor Peter Buttigieg was about to announce his candidacy for president of the United States. The thirty-seven-year-old war veteran, former Rhodes Scholar, and openly gay Christian from the Midwest had only seven years of political experience as the mayor of South Bend, Indiana. Just a few years earlier, his city had been called one of the top ten “dying cities” in America.1 Buttigieg was not the typical presidential candidate, and the odds were not in his favor, but he felt he could unite Americans at a divisive time in the nation’s history. Could he leverage the power of story to rally people behind his vision?

Two years earlier, Buttigieg had participated in the inaugural cohort of the Bloomberg Harvard City Leadership Initiative, where he had received training and then coached other mayors in the art of “public narrative.” The goal of public narrative, Buttigieg and his fellow mayors learned, is not to get standing ovations but rather to motivate people to take collective action. While that may seem a high bar, a recent paper in Academy of Management Learning and Education by Marshall Ganz, Julia Lee Cunningham, Inbal Ben Ezer, and Alaina Segura argues that this practice can be learned.2 It defines public narrative as a way to access, articulate, and communicate shared values and provides a framework for harnessing its power to strengthen community ties and create leadership capacity.

Stories of “hurt” (struggle, injustice) and “hope” (belief in possibility) help people realize why they care about what they care about—and how they can find the courage to do something about it. Effective stories focus on specific moments when a protagonist confronts a challenge and finds the emotional resources to take it on. Details allow listeners to empathize with the protagonist, feeling the hurt and the hope, and thus learning an experiential “moral,” a lesson of the heart.

Ganz’s framework links together a “story of self,” a “story of us,” and a “story of now” as a leadership practice connecting the leader, their constituency, and the need to act now. The leader shares the personal experiences that shaped their motivation, the shared experiences that connect members of the constituency to each other, and the urgent challenges and hopes that can enable a community to choose action.

While anyone who is called to social action can learn to practice public narrative, they cannot do so by simply reading a text book. Learning to practice the craft is like learning to ride a bike: you get on, you fall, and you either go home or find the courage to try again. The study outlines the following four-step teaching and learning process: First, an educator explains the concepts; then the educator models the practice; third, participants craft and share their stories, and also receive feedback from their peers and coaching from an expert facilitator; and, finally, participants debrief their experiences. The experience of articulating one’s story, receiving coaching, and helping peers to improve is an empowering leadership development practice for everyone involved.

After Buttigieg participated in the public narrative training offered by the Bloomberg Harvard City Leadership Initiative in 2017, he and his team decided to bring storytelling to South Bend. They hoped to strengthen community ties and rewrite the city’s narrative from one of post-industrial decline to a new story of resurgence and civic purpose. Over a two-day period, a group of nearly fifty city staff members, partner organizations, and community organizers came together for a workshop based on the public narrative framework. As part of the session, Buttigieg delivered his own public narrative and coached a team of participants.

The workshop generated multiple successes: The director of the public library told a powerful story about why books were so meaningful to her and the community, which helped her secure a $5 million investment. A representative from the education department later leveraged her skills to communicate her vision for the city’s public schools and win a seat on the school board. Many participants reported a better understanding of their peers’ motivations and a greater connection with the mayor’s vision for South Bend.3

Buttigieg’s use of public narrative not only strengthened his local leadership, it also helped shape his story as a history-making presidential candidate. He launched his campaign with a “story of self” rooted in the isolation he felt growing up as an intellectual, gay young man in a midwestern city recovering from economic decline, a feeling that appeared to resonate with voters who felt anxious about their own place in America. He brought to life a “story of us” through vignettes that illustrated common challenges: natural disasters, the difficulty of getting health care, and an uncertain economic future. Finally, his “story of now” depicted the 2020 election as a crucial moment of generational change where voters had the power to come together to elect a president who shared their experiences and values and who could help prepare the country to meet these challenges for decades down the line.

Buttigieg won the Iowa caucuses and came in second in the New Hampshire primaries. Although he later dropped out of the presidential race, he had made a lasting impression as a talented newcomer and was seen as a rising star in the Democratic Party. The New York Times4 and other national media largely credited his success to his ability to leverage the power of story to connect with voters and establish a sense of shared identity and purpose. In December of 2020, president-elect Joe Biden nominated Buttigieg for Secretary of Transportation, making him the youngest person to serve in that role.

What makes this framework valuable to community organizers and political leaders alike is that it focuses on building relationships, enabling collective action, and growing a movement: it helps leaders craft their own public narratives even as they learn to develop this skill in others. To be effective at building authentic relationships, leaders must be willing to be vulnerable. Sharing their personal stories of hurt and hope motivates others to find the courage to share theirs.

When asked if public narrative was not just another form of packaging or branding, Harvard student Jayanti Ravi noted: “It is not about applying a gloss from the outside; it is about bringing out the glow from the inside.” Public narrative is not a recipe for slick communication, political marketing, or personal success—it is storytelling in service of collective action. Telling one’s own story is only a beginning; by enabling others to master the practice, leadership capacity for positive social change can expand exponentially.

1 MainStreet, “America’s Dying Cities,” Newsweek, January 21, 2011, https://www.newsweek.com/americas-dying-cities-66873

2 Ganz, an author of this piece and the associated academic article, is a Harvard sociologist with deep experience in community organizing. Building on his time both in the field and the classroom, he has developed a framework for learning, practicing, and teaching public narrative. He and Sarah ElRaheb lead the Initiative’s public narrative training programs for mayors and other city leaders.

3 Santiago Garces, former South Bend, Indiana Chief Innovation Officer, interview by authors, September 30, 2022.

4 Alexander Burns, “Pete Buttigieg’s Focus: Storytelling First. Policy Details Later,” The New York Times, April 14, 2019.

Academy of Management Learning & Education

The New York Times

The New York Times

Bloomberg Harvard City Leadership Initiative

More Resources Like This