“Inter-city collaboration: Why and how cities work, learn, and advocate together”

Global Policy Journal

Action Insights

Last Updated

Topic

Collaboration

Location

United States

Inter-city collaborations are on the rise, but what value do they produce for cities? A study supported by the Bloomberg Harvard City Leadership Initiative explores how city leaders can make informed decisions about participation.

Read the Action Insights below, or download as a PDF for use later.

Inter-city collaborations (ICCs) have existed throughout history. Before national governments consolidated power, city-states collaborated on security and trade. Today, cities large and small partner up to negotiate waste management contracts, exchange policy ideas, fight a global pandemic, and tackle climate change. By joining forces, cities can achieve economies of scale, learn from each other, solve collective action problems, and amplify their voices on the national and global stages.

But participating in an ICC is not without costs. City leaders are busy, and their time is a scarce and valuable resource. A study published in Global Policy describes how and why cities collaborate and lays out a framework for understanding the main forms of value ICCs deliver. The findings can help city leaders:

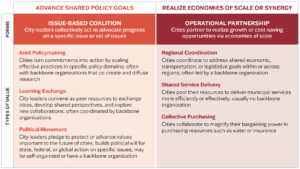

Desk review, surveys, and interviews with dozens of city leaders and managers of ICCs in the U.S. and abroad showed that ICCs are widespread, on the rise, and focused on cities’ top priorities. Table 1 distinguishes two broad categories. In operational partnerships, cities collaborate to realize growth or cost-saving opportunities via economies of scale. These collaborations can deliver value in the form of regional coordination, shared service delivery, or collective purchasing. In issue-based coalitions, city leaders act collectively to advocate for specific issues. These ICCs promote joint policymaking, learning exchanges, or political movements.

For example, the Utah Telecommunications Open Infrastructure Agency (UTOPIA) is an operational partnership that facilitates shared service delivery. When telecom companies refused to service their area, UTOPIA enabled municipalities in Utah to develop an advanced fiber optic network. Cities Coalition for Digital Rights, on the other hand, is a global issue-based coalition that facilitates learning exchange and helps cities develop policies around access to technology and data security.

Table 1

Some ICCs advance strategic priorities that span city limits (e.g., transportation) or require innovation (e.g., broadband access, workforce development). Other ICCs allow cities to lower the cost of services and invest in technology they could not otherwise afford. Still other ICCs allow senior leaders—not just mayors—to learn, network, benchmark, and exchange ideas.

According to both members and organizers of ICCs, factors for success include shared values, dedicated staff or a backbone organization, and involving city leaders in strategy development. Factors that hinder success include politicization of issues and dependency on the commitment of elected leaders. For example, C40, which began as a climate-change initiative at the Mayor of London’s office, has succeeded in part because it secured independent funding to become its own organization with specialized staff. By contrast, the Fairfield Five, a collaboration of five towns in the suburbs of New York City that worked to draw companies out of the city by showcasing the towns’ assets, had each town designate a staff member and add the ICC to their existing duties. Without dedicated staff, the collaboration ceased.

Today’s city leaders face challenges ranging from inter-generational poverty to climate change, and from public health emergencies to a changing social and political landscape. ICCs give cities the (purchasing) power to punch above their weight, the learning space to create and discover innovative policy solutions, and the organizational vehicle to develop a unified voice in state, national, and global policy debates. On the other hand, city leaders are often stretched thin, and the proliferation of ICCs can add to the stress of competing commitments. Being intentional about joining an ICC, articulating what success looks like and how it will be measured, and recognizing the factors that help and hinder collaborative success can help city leaders determine if becoming a member is in their city’s best interest.

Among other things, city leaders should bear in mind:

Global Policy Journal

Stanford Social Innovation Review

Stanford Social Innovation Review

Bloomberg Harvard City Leadership Initiative

More Resources Like This